Figure 1: Contents of a bag of worked flint given to me by John to draw

While reflecting on my first attempt at flint knapping at the hand-axe making workshop I was struck by how unintuitive the process of flint knapping is. For a novice like myself, the act of knapping flint with the objective of producing a recognisable tool was not only difficult to physically do, but almost impossible to conceptualise. I assumed that because I had some understanding of the theory of flint fracture mechanics it would come naturally to me. It is also likely that, on some level, I had assumed that because flint-working is perceived as so simple and such a fundamental part of the ‘natural’ behaviour of hominins, that the leap from theory to action would be small. But, as became obvious to me after attending the workshop, it is not just the development of physical knapping techniques that requires practice, but the very ability to understand the material.

It is easy to underappreciate the challenge of flint knapping before trying it out for yourself, particularly as the material itself feels unfamiliar. But nonetheless, just as Laura wrote about in the previous blog post, being surrounded by others – being able to watch what they are doing, mimic them or ask them questions – was also how I was able to take the very first steps in learning what to do. The social aspect of flint knapping led me to reflect on an essay I wrote during my Master’s course on the utility of typologies based on the chaîne opératoire (typologies are methods used to classify artefacts and the chaîne opératoire refers to the method of understanding artefacts based on how they are made, rather than what they look like).

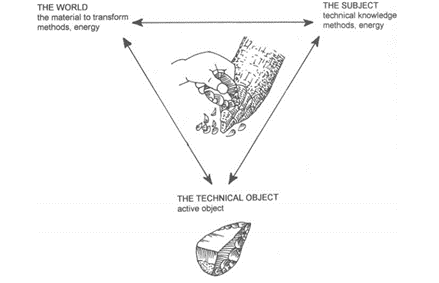

Figure 2: The relationships inherent in lithic tool manufacture (Geneste and Maury, 1997)

The chaîne opératoire appealed to me as it moves away from thinking of artefact types as static and provides room to think about why and how artefacts change over time. Proponents of typologies based on the chaîne opératoire argue that the methods by which people make things – their learned physical habits – are a more accurate indicator of cultural identity than artefact form or design, which can be replicated with different techniques (Kuijpers, 2018; Manclossi and Rosen, 2019; Roux, 2019; Tostevin, 2011). Crucially, physical habits are learned from an early age from skilled members of the community and, therefore, are a product of social relationships. Taking part in the flint knapping workshop allowed me to better understand knapping as a social activity, and thereby the relevance of the chaîne opératoire in artefact analysis. This was especially the case once I realised that ‘skill’ refers not only to the physical process of doing something, but the very way we understand it.

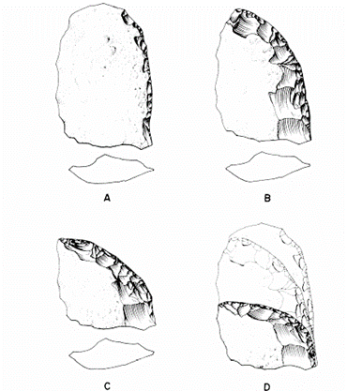

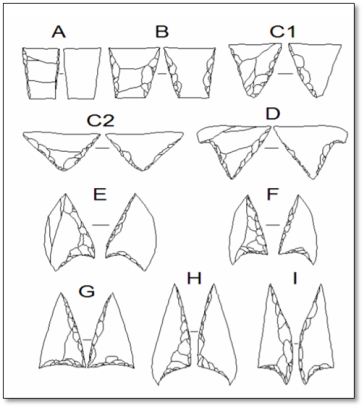

The principles of the chaîne opératoire have been used to inform lithic typologies for decades. Harold Dibble’s (1987) study of scraper morphology is the quintessential example of this in demonstrating the importance of understanding knapping as a process, as opposed to simply being able to identify the end-product (Figure 3). Vital for studies of lithic chaîne opératoires is the analysis of debitage, which provides valuable information on the techniques used to work a core. However, the typologies currently used in British scholarship on lithics are designed to describe the exact form and shape of clearly identifiable tools (see Figure 4). There remains no coherent vocabulary to describe the debitage produced in the knapping process, and we continue to rely on the vague terms, ‘blade’, ‘flake’, ‘chip’, ‘chunk’, ‘spall’, which tell us very little about the techniques used in their production. Through the process of experimental knapping, and watching how much debitage was produced (versus how many typologically clear ‘end-products’ were produced) I began to reflect again on how much more detailed and meaningful the archaeological record could be if we moved away from ‘morphological types’ and focused instead on the processes by which things are made. For, if this were the case, there would be a much greater incentive to describe debitage in detail.

Figure3: The different phases in the reduction of a scraper, which were originally described as separate ‘types’ (Dibble, 1987: 112)

The problem with British typologies is felt especially in commercial archaeology, where the description of artefacts by type is often the only information recorded about them. Commercial archaeology works on the premise that the destruction of archaeology can be mitigated by the production of archives, or “preservation by record” (Andrews et al, 2000: 527). This means that the archaeological report produced at the end of each excavation is the only way in which archaeological knowledge produced can be kept and disseminated. It is therefore especially important that such reports use accurate and meaningful typologies. Moreover, given that commercial companies are often under strict time and financial pressure to complete report writing (Davies, 2017: 185), the use of typologies to describe lithics (typically in an Excel spreadsheet) is generally preferred to the time-consuming methods of measuring and drawing.

Figure 4: Clark’s (1934) typology of PTD arrowheads, reproduced by Ballin (2021: 28)

As someone who is interested in questioning the typologies we currently use in lithic scholarship, but is also keenly aware of their practical necessity, especially in the world of commercial archaeology, attending John’s hand-axe making workshop was fascinating and thought-provoking. My goal in learning to knap flint is not to make impressive flint artefacts. Instead, I am most interested in understanding how flint works, and the choices a knapper makes in order to shape their material. I hope that the result of this will be an ability to better read those choices from flint assemblages, with a view to learning about how patterns of craft production have changed throughout prehistory.

References:

Andrews, G., Barrett, J.C. and Lewis, J.S., 2000. Interpretation not record: the practice of archaeology. Antiquity, 74(285), pp.525-530.

Ballin, T. 2021. Classification of Lithic Artefacts from the British Late Glacial and Holocene Periods. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Davies, D. 2017. The Development of Archaeological Post-Excavation within British Professional Archaeology. BAJR Guide Series.

Dibble, H. 1987. The interpretation of Middle Palaeolithic scraper morphology. American Antiquity. 52: 1. 109-117

Geneste, S. and Maury, J. 1997. Contributions of Multidisciplinary Experimentation to the Study of Upper Palaeolithic Projectile Points. In Knecht, H. (ed.) Projectile technology. New York; London: Plenum Press 165-189

Kuijpers, M. 2018. A sensory update to the Chaîne Opératoire in order to study skill: perceptive categories for copper-compositions in archaeometallurgy. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 25(3): 863-891.

Manclossi, F, and Rosen, S. 2019. Dynamics of Change in Flint Sickles of the Age of Metals: New Insights from a Technological Approach. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 7. 6-22

Roux, V. 2019. Ceramics and Society: A Technological Approach to Archaeological Assemblages. Cham, Switzerland: Springer

Tostevin, G. 2011. Levels of Theory and Social Practice in the Reduction Sequence and Chaîne Opératoire Methods of Lithic Analysis. PaleoAnthropology. 351-375