I realised a good while ago that I am interested in categories and boundaries. This is because of my own experience, being ‘half-caste’ in the 60s, 70s and 80s, ‘mixed race’ in the 90s and by the early 2000s I had become ‘dual heritage’. These are all what are termed ‘etic’ or outside categories, how society has characterised me. An ’emic” or internal category would be how I characterise myself, and that would be as ‘Mancunian’. More than just abstract concepts, these labels have implications for the differing ways I have understood myself and been treated in the real world, hence my interest.

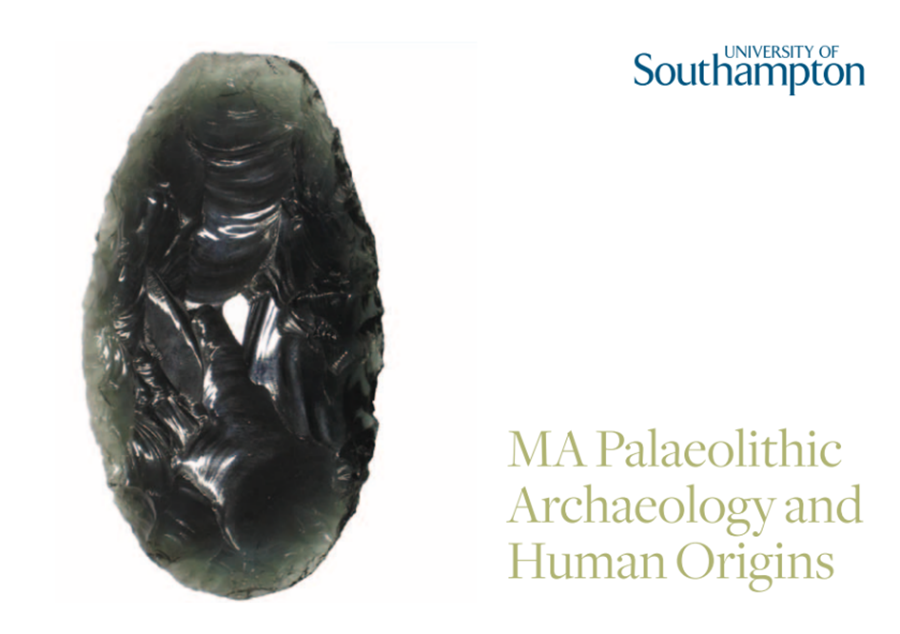

Onto handaxes. I am really liking this most recent offering. It is made from the largest piece of slag glass kindly provided by the folks at Salford Archaeology. I have left the base as is, referencing where it has come from, and in relation to the worked section, I like the thinned serrated edge on both sides. It would make a great cutting tool, and I am super pleased with this one.

So form and potential function if you like, mirror a Palaeolithic handaxe. However, the material it is made from, a slag glass block excavated from a factory in Manchester, anchors it very much in the modern industrial period. It has two, temporally contradictory etic heritages, or narratives captured within one beautiful object.

So what about its emic identity? I don’t think the handaxe itself can tell us, but through my visual and haptic engagement with it I would say it is pretty special. It works for me on every level, and it feels like I have expressed something of myself within the production of this object. It was satisfying to make and I am happy that I have this ability to create things of beauty such as this. And I think that its dual heritage adds to its aesthetic and doubles its narrative value. Happy days!