Experimental production of stone tools

Last week Nacho, Howard and Jex made some time to record the smashing and melting processes for the glass collected from the bottle tip. Above you can see a birds eye view of Nacho’s home made kiln that we were using for the experiment.

In total we had six clay moulds lined with aluminium takeaway containers. The take away containers function was to stop the melting glass adhering to the clay mould. In relation to the kiln we had an upper and lower section, and were interested to know if location within the kiln was going to be a factor. As you can see, we also had glass of different colours and Nacho thought the milk glass, based upon its density, would be the most difficult to melt.

The above photograph shows the kiln just as it reached 1000 degrees. I was told in Spain that glass melts at around 850 degrees, and so in theory 1000 degrees would be more than enough. However, it was possible to see into the kiln, and although the glass had adopted a sheen, it clearly had not yet liquified. So we carried on upping the temperature.

Above is the sample Nacho had made so that we could pull it out and see how things were progressing. When he pulled this out the glass was red hot, however, as it cooled it became apparent that the clear glass fragments had liquified whilst those of milk glass were still recognisable as fragments. The differing colours were indeed behaving differently.

I had to be in university by 5pm and so at 4pm Nacho switched off the heat source and allowed the kiln to start the cooling process naturally. We could see that some of the glass had indeed melted, whilst other glass hadn’t. The mix above of clear and milk glass had the texture of a rice cake, rather than the smooth and solid block we were looking for. On the plus side, it did release from the clay mould easily, in spite of the fact that the aluminium tray had melted.

This blue example was perhaps exactly the opposite. It seemed to have melted well, although upon close inspection a crack could be see running diagonally across the block.

Because this looked like a promising candidate we tried to release it from the clay mould, but this one had attached itself to the clay, and you can see the results of our attempts.

This blackcurrant glass also looked promising, but the thing to note here is the bubbles. This must have cooled very (too) rapidly to capture the bubbles like this. Perhaps, if we don’t want bubbles then the heat should be turned down rather than turned off in order to make the cooling process more gradual.

This second blue one looked similar to the blackcurrant glass on the surface, however, when I tried to release it from the mould the internal structure was revealed, and that also contained bubbles. None of the six slabs were suitable for Knapping, so what did we do wrong?

I think we should have kept increasing the temperature to above the maximum of 1018 degrees that we got to on the day, in order to identify when the most difficult milk glass will melt. A second thing is to slow the cooling process so that bubbles have the chance to settle before the glass starts to solidify. We also need to consider alternative mould methods, as the aluminium takeaways, whilst not the main issue, didn’t help by melting.

We didn’t get what we wanted, but we did get plenty to think about!

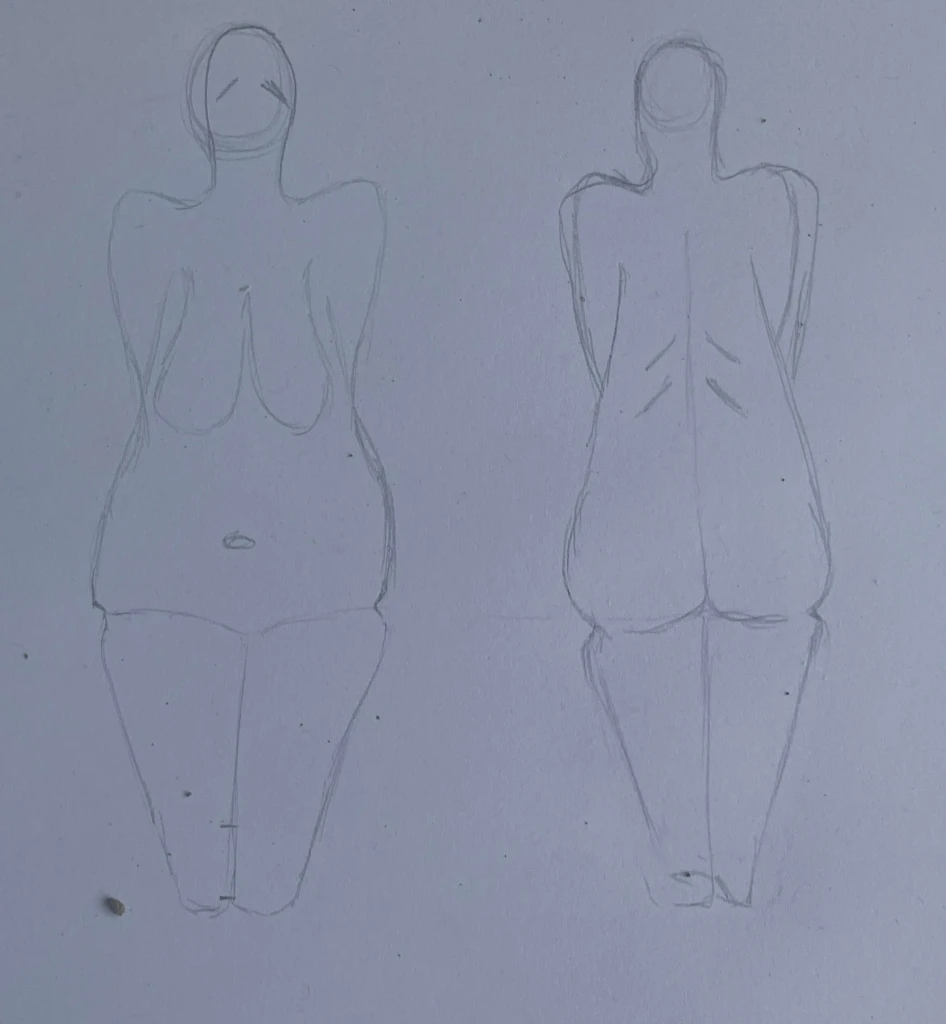

This week we had an experimental session with second-year ‘Themes’ students in Chester making some clay Palaeolithic Dolni Vestonice ‘venus’ figurines (and associated wolverines and bears). Nacho came over with me from Manchester and the topic we used the making process to explore was that of Personhood. How we as modern westerners understand the category, but also thinking about how people in the Palaeolithic past may have done so. And a number of interesting ideas emerged.

A 2017 scan (see link below) of the ‘venus’ revealed that it had been made from one piece of material, as opposed to having bits stuck on to create the arms, legs, breasts etc. This was something Paul Thomas talked about in a previous workshop and demonstrated how squeezing the clay brought out particular shapes that could then be ‘pulled’ into shape. This contrasted to the approach many of the students initially took this week, adding clay to the models to build them up. I think it is fair to say that everybody (including Nacho) had difficulties creating a model ‘venus’ that was correct in size and form. However, after initial difficulties, and once people had got a feel for the materials a menagerie of animals emerged. This cat for example seems to have started out as a wolverine or bear, but then morphed into a cat. People seemed to find it much easier to create a shape from the clay that corresponded with an animal they knew, rather than emulate photographs of the originals. As Nacho pointed out, that is exactly what people in the past were doing, and so in many ways figurines like the cat below are more representative of the original process than a super accurate wolverine or bear replica.

In relation to the ‘venus’ we asked people to draw the figurine first, as a way of seeing the key elements before embarking upon the making process. In the discussion section at the end Elowyn said that she didn’t see herself in the figurine, and felt as though it was referencing an older female form. Jacob suggested it represented a woman’s body after having gone through the process of childbirth, and we all agreed that the lack of facial detail meant it wasn’t an individual portrait but representing a category of women. This was interesting from the personhood perspective because it suggests Palaeolithic womanhood comprised different facets perhaps organised around age bands and the process of childbirth.

It was also interesting that towards the end of the session Elowyn made Victoria a present of a miniature bear, and then gifted it to her. This allowed us to think about the potential of the original ‘venus’ having been a gift, and about what possible qualities may also have been given along with the figurine? We had discussed the Soffer (et al. 1993) paper arguing that the figurines may have been deliberately exploded during the firing process for divination purposes. Developing the ideas of Soffer (et al. 1993: 39) we thought about whether the gifting of the figurine could have been intended to ensure safe childbirth?

For me, the key idea that emerged from the session was again about the making process and its relationship with the human hand. Squeezing the material allows certain shapes to emerge and these shapes may resemble recognisable animals or person categories. This general similarity can then be developed by literally pulling the material into shape. That the the creation is then fired and potentially exploded provides a really interesting blend of dramatic creation and destruction narratives. And so, far from Nacho and myself ‘delivering knowledge’, it was very much the making and sharing of ideas part of the session that resulted in it being so interesting and enjoyable.

And at this point it is probably apposite to introduce my own personal favourite, Owain’s cheeky bear, and thank Nacho for facilitating the making process and Jacob for being official photographer on the day.

Papers

Soffer, O., Vandiver, P., Oliva, M., and Seitl, L. 1993. Case of the exploding figurines. Archaeology Vol.46(1) pp.36-39.

Links

On our Herefordshire fieldwork project we camp on the local Dorstone village playing fields behind which runs an old straight track. On a dog walk last year I noticed a section that had some inclusions with conchoidal fractures.

I stored this in my memory bank, and this year ended up going on a super impromptu walk with a group of students interested in lithics. The aim was to introduce them to the art of finding knappable materials in the landscape (something I am getting good at).

Anyway, as well as an opportunity to all get to know each other a little better, it turned out to be a surprisingly enjoyable material locating and testing exercise.

I told Tim Hoverd, Herefordshire County archaeologist, about our adventure and he pointed out that this particular old straight track used to be a railway line, hence the glass slag that we were finding. I wanted to end this post with some kind of witty Alfred Watkins reference. However, I have now ended up reading about the Golden Valley Railway on Wikipedia. C’est la guerre.

I have been away for the whole of July on fieldwork in Herefordshire, and one element was the excavation of a scheduled ancient monument, Arthur’s Stone. Associated with this was an outreach project designed to engage locals with the excavation. Enter Martin Lewis.

Martin used to farm in the local area and when he heard we were up at Arthur’s Stone he brought this massive Neolithic axe up to show us. It was found by him in 1984 during a potato harvest, and only three fields away from where we were currently working.

Its main attribute was size, being flaked and patinated but not really polished. However, in areas with what looked like recent chips the material looked familiar, and it wasn’t flint. It reminded me of the material from the ‘axe factory’ that I visited in the Llyn Peninsula earlier this year.

Indeed, Martin brought up a report about the find which stated that the material was from South Wales, and it also suggested that what I read as recent chips were in fact original flake removals. I am not sure why they would say that as it makes no sense to me. I would say it was produced, it patinated, and more recent accidental chipping, perhaps by the potato harvesting machine has revealed the original material. That is my reading and it would be interesting to know why the authors thought differently however they presented no further explanation.

What is interesting to me though is that although I couldn’t tell you the kind of stone it was made from, I could tell straight away the approximate geographical area that the stone had come from. I think this aspect may well have been another important attribute of this object during the Neolithic.

Figure 1: Contents of a bag of worked flint given to me by John to draw

While reflecting on my first attempt at flint knapping at the hand-axe making workshop I was struck by how unintuitive the process of flint knapping is. For a novice like myself, the act of knapping flint with the objective of producing a recognisable tool was not only difficult to physically do, but almost impossible to conceptualise. I assumed that because I had some understanding of the theory of flint fracture mechanics it would come naturally to me. It is also likely that, on some level, I had assumed that because flint-working is perceived as so simple and such a fundamental part of the ‘natural’ behaviour of hominins, that the leap from theory to action would be small. But, as became obvious to me after attending the workshop, it is not just the development of physical knapping techniques that requires practice, but the very ability to understand the material.

It is easy to underappreciate the challenge of flint knapping before trying it out for yourself, particularly as the material itself feels unfamiliar. But nonetheless, just as Laura wrote about in the previous blog post, being surrounded by others – being able to watch what they are doing, mimic them or ask them questions – was also how I was able to take the very first steps in learning what to do. The social aspect of flint knapping led me to reflect on an essay I wrote during my Master’s course on the utility of typologies based on the chaîne opératoire (typologies are methods used to classify artefacts and the chaîne opératoire refers to the method of understanding artefacts based on how they are made, rather than what they look like).

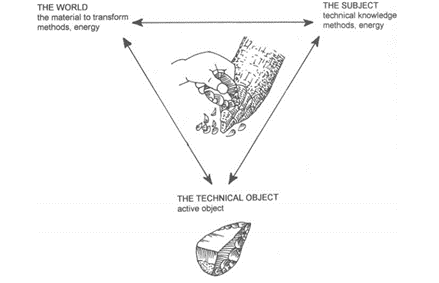

Figure 2: The relationships inherent in lithic tool manufacture (Geneste and Maury, 1997)

The chaîne opératoire appealed to me as it moves away from thinking of artefact types as static and provides room to think about why and how artefacts change over time. Proponents of typologies based on the chaîne opératoire argue that the methods by which people make things – their learned physical habits – are a more accurate indicator of cultural identity than artefact form or design, which can be replicated with different techniques (Kuijpers, 2018; Manclossi and Rosen, 2019; Roux, 2019; Tostevin, 2011). Crucially, physical habits are learned from an early age from skilled members of the community and, therefore, are a product of social relationships. Taking part in the flint knapping workshop allowed me to better understand knapping as a social activity, and thereby the relevance of the chaîne opératoire in artefact analysis. This was especially the case once I realised that ‘skill’ refers not only to the physical process of doing something, but the very way we understand it.

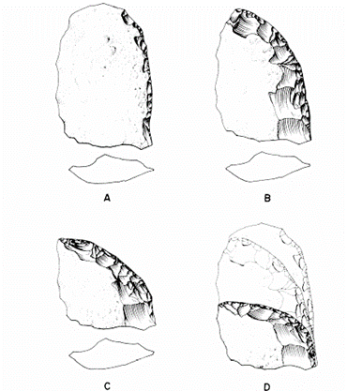

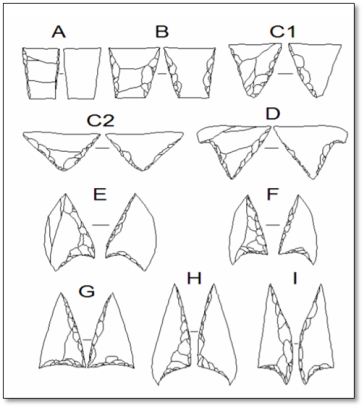

The principles of the chaîne opératoire have been used to inform lithic typologies for decades. Harold Dibble’s (1987) study of scraper morphology is the quintessential example of this in demonstrating the importance of understanding knapping as a process, as opposed to simply being able to identify the end-product (Figure 3). Vital for studies of lithic chaîne opératoires is the analysis of debitage, which provides valuable information on the techniques used to work a core. However, the typologies currently used in British scholarship on lithics are designed to describe the exact form and shape of clearly identifiable tools (see Figure 4). There remains no coherent vocabulary to describe the debitage produced in the knapping process, and we continue to rely on the vague terms, ‘blade’, ‘flake’, ‘chip’, ‘chunk’, ‘spall’, which tell us very little about the techniques used in their production. Through the process of experimental knapping, and watching how much debitage was produced (versus how many typologically clear ‘end-products’ were produced) I began to reflect again on how much more detailed and meaningful the archaeological record could be if we moved away from ‘morphological types’ and focused instead on the processes by which things are made. For, if this were the case, there would be a much greater incentive to describe debitage in detail.

Figure3: The different phases in the reduction of a scraper, which were originally described as separate ‘types’ (Dibble, 1987: 112)

The problem with British typologies is felt especially in commercial archaeology, where the description of artefacts by type is often the only information recorded about them. Commercial archaeology works on the premise that the destruction of archaeology can be mitigated by the production of archives, or “preservation by record” (Andrews et al, 2000: 527). This means that the archaeological report produced at the end of each excavation is the only way in which archaeological knowledge produced can be kept and disseminated. It is therefore especially important that such reports use accurate and meaningful typologies. Moreover, given that commercial companies are often under strict time and financial pressure to complete report writing (Davies, 2017: 185), the use of typologies to describe lithics (typically in an Excel spreadsheet) is generally preferred to the time-consuming methods of measuring and drawing.

Figure 4: Clark’s (1934) typology of PTD arrowheads, reproduced by Ballin (2021: 28)

As someone who is interested in questioning the typologies we currently use in lithic scholarship, but is also keenly aware of their practical necessity, especially in the world of commercial archaeology, attending John’s hand-axe making workshop was fascinating and thought-provoking. My goal in learning to knap flint is not to make impressive flint artefacts. Instead, I am most interested in understanding how flint works, and the choices a knapper makes in order to shape their material. I hope that the result of this will be an ability to better read those choices from flint assemblages, with a view to learning about how patterns of craft production have changed throughout prehistory.

References:

Andrews, G., Barrett, J.C. and Lewis, J.S., 2000. Interpretation not record: the practice of archaeology. Antiquity, 74(285), pp.525-530.

Ballin, T. 2021. Classification of Lithic Artefacts from the British Late Glacial and Holocene Periods. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Davies, D. 2017. The Development of Archaeological Post-Excavation within British Professional Archaeology. BAJR Guide Series.

Dibble, H. 1987. The interpretation of Middle Palaeolithic scraper morphology. American Antiquity. 52: 1. 109-117

Geneste, S. and Maury, J. 1997. Contributions of Multidisciplinary Experimentation to the Study of Upper Palaeolithic Projectile Points. In Knecht, H. (ed.) Projectile technology. New York; London: Plenum Press 165-189

Kuijpers, M. 2018. A sensory update to the Chaîne Opératoire in order to study skill: perceptive categories for copper-compositions in archaeometallurgy. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 25(3): 863-891.

Manclossi, F, and Rosen, S. 2019. Dynamics of Change in Flint Sickles of the Age of Metals: New Insights from a Technological Approach. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 7. 6-22

Roux, V. 2019. Ceramics and Society: A Technological Approach to Archaeological Assemblages. Cham, Switzerland: Springer

Tostevin, G. 2011. Levels of Theory and Social Practice in the Reduction Sequence and Chaîne Opératoire Methods of Lithic Analysis. PaleoAnthropology. 351-375

Flint working was an entirely new experience for me but getting to approach the material in a group environment made it a far less daunting task. I have knapped before, but only with glass bottles – easy to acquire as a student and much cheaper than flint! Glass behaves itself generally and you can predict where and when it will facture (mostly) making it a great starting material for knappers. I have no right to claim any decent knowledge of knapping or the skills that come with it, but I have managed, after many (many!) breakages, to form a neat little collection of glass arrowheads for myself.

I felt somewhat confident going into the flint knapping workshop John was hosting. I had seen the flint before, but I had never worked with it. We were given a detailed run through of how the flint reacts and how we should react to the flint, thinking of it as working together rather than just working on a material. Alice la Porta showd a video of a professional American knapper who created a beautiful flint axehead in just 25 strikes – a rather impressive and somewhat intimidating display of skill.

We started trying to make our own scrappers after a demonstration from John, and it’s fair to say mine did not turn out so well. I began with a decent palm-sized piece of flint which ended up about the size of my thumb with no real clear edge that could be used as a scraper. I tried again and again with flint flakes I found on the floor (I didn’t want to waste any good bits with my terrible practice blows) but didn’t have much luck. Flint was far harder to work with than I had anticipated and certainly much harder to knap than glass. I spent a good hour or so working on scraps trying to make a scraper before we moved onto looking at handaxes. Oddly, working towards a handaxe with the flint was much easier for me – I could visualise what I wanted a lot better and working with a larger piece of flint made me much more confident in my hits with the soft and hard hammers. Perhaps it was because I was used to working towards a similar goal that I set myself when making glass arrowheads, getting full surface removal of cortex and shaping the material, that I found making the flint handaxe easier to understand. This does not mean, however, that I had any clue what I was truly doing and was solely relying on the flint to help me and suggest areas to work on next. I did, in the end, leave with a beautiful handaxe I am very proud of (after some help from John).

What I took away from this experience was that knapping does not have to be a lone effort. Beginner knappers, such as myself, need help and guidance from the more experienced, and even other beginners who might be catching on to some of the tricks faster. Though it is a personal creation does not mean a community effort cannot go into its manufacturing. I personally believe the experience would not have been as enjoyable had I been left alone in a room with an instructional video to watch and learn from. People help people when it comes to these kinds of workshops, whether that’s the teacher or other learners, community is an important part of the learning and creation process.

It took a long time for me to get used to working with the characteristics of flint as I was so used to glass. I had to relearn a lot of what I knew about knapping, but it was an eye-opening experience as it just goes to show how skills can always be developed and adapted to new (and more difficult) materials. This workshop was an excellent chance for me to make something I could be proud of, but also learn through others: there was such a variety of people at the workshop, professors, other students, commercial archaeologists, and we all had different ways of approaching the task. Getting to watch others learn and practice is, for me, one of the best ways to develop new skills and enjoying doing so.

Last Saturday I took part in a session at the Whitaker Museum in Rossendale. My friend, Stephen Poole, had been invited to talk about the Pioneers of Rossendale: the Late Upper Palaeolithic and Early Mesolithic populations that left behind in the Pennines their calling cards, in the form of flint tools.

However, the pioneers in question were also the late nineteenth and early twentieth century researchers whose stone tool collections ended up in local museums like the Whitaker. Whilst working through these collections Stephen had identified half a Mesolithic shale bead, and because of that bead fragment asked if I wanted to run a Mesolithic bead and pendant making workshop after his talk.

I was happy to help but I couldn’t do the cordage aspect of the process, so I organised the workshop logistics with Jane from the museum, and two of our super competent third year undergraduate students, Jordan and Laura, ran the whole session! This meant that I could sit back and get some cordage making practice in, and in doing so I got a little carried away.

Anyway, I had made this (not Mesolithic) knife a good while ago and at the time noted the small chalk filled hollow. I poked out the chalk and thought it would be good to thread some cordage through at some point so It could be worn around the neck. That is what I had in mind whilst making cordage at the Whitaker.

So today I pulled out the knife and used the cordage to produce my lithic necklace. The cordage is too long and I don’t wear necklaces, but I love the aesthetic of bringing the two technologies together. Anyway, thanks to Jordan (cordage), Laura (pendant) and Stephen (lecture) for doing the heavy lifting.

And also to Jane from the Whitaker for organising the microphone, stickers for name badges, and most importantly, lunch!

We had an excellent handaxe making workshop in the labs yesterday, and I will do a separate post about it when I get some feedback from participants. This post is about one small part of the session. Before the handaxe making started in earnest we watched a ten minute video of an American knapper produce a large handaxe from a flat tablet of Texas chert.

The American knapper was highly skilled and produced a long symmetrical handaxe within something like 25 removals. Impressive. However, I lost interest early on. We had looked at the handaxes in the teaching collection and these real examples were much less refined. In our session we were also using knobbly flint nodules from Norfolk with fossils, holes and differential texture throughout.

The video was a performance of control by a highly skilled knapper using high quality material of an optimum shape and size. The factors being controlled, size, shape, material quality, were exactly those we were negotiating. To me the video was a sales pitch to archaeologists looking for machine like knappers to take part in ‘scientific’ experiments.

However, our exploratory negotiations with less than ideal materials resulted in artefacts much closer to the examples in the teaching collection. The handaxe in the photos was made before the workshop from a large flake with a big hole, small fossil, and course grained sections. My perspective is perhaps related to a current obsession with this brilliant track by the band James, describing the messiness of life and how we engage, make mistakes, change tack, and that we are ultimately, just getting away with it.

Whilst I felt the American knapper’s video was a performance of control, our knapping session was more like the performance of being human, and I loved it.

© 2026 Learning Through Making. All Rights Reserved.