What is aesthetics? According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) Online the word aesthetic is derived from Ancient Greek and relates to sense and perception. In relation to the French noun esthétique the OED Online provides this explanation from 1819, a: ‘set of rules or standards by which art is judged’. Yesterday my ‘workshops’ friend, Laura Thompson organised for us a handaxe making session for half a dozen academic staff and students in the Archaeology labs. My ‘Mesolithic’ friend, Stephen Poole made a trip in from Rochdale to help me out with the teaching process. In the discussion session at the end the subject of aesthetics came up a couple of times.

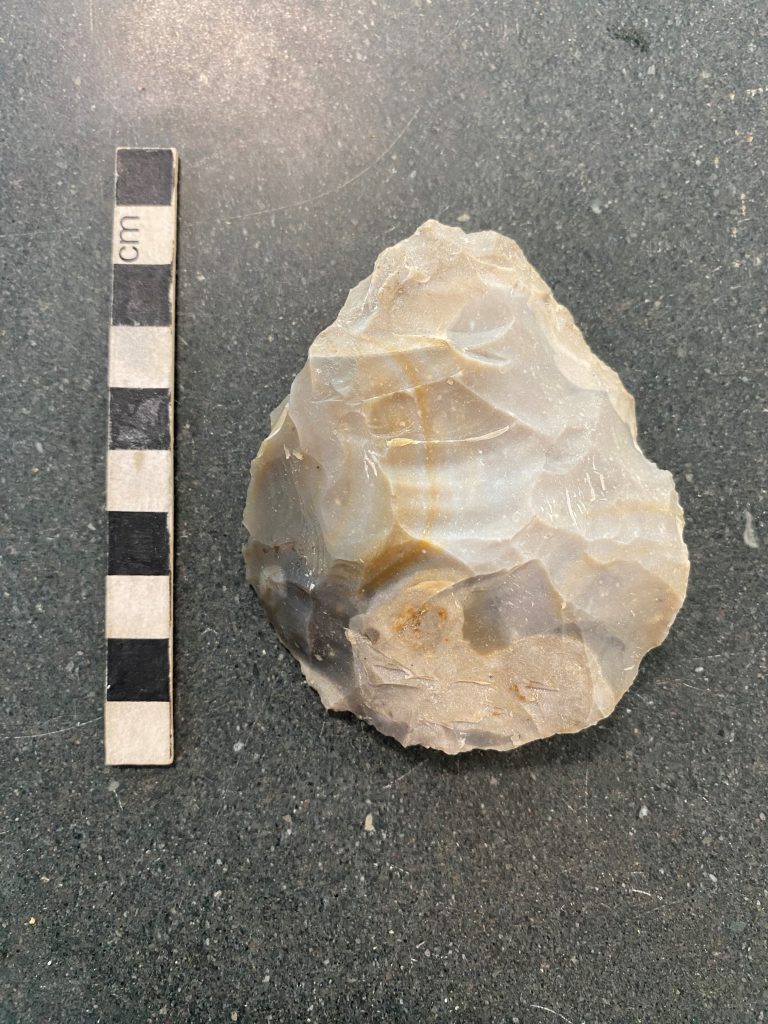

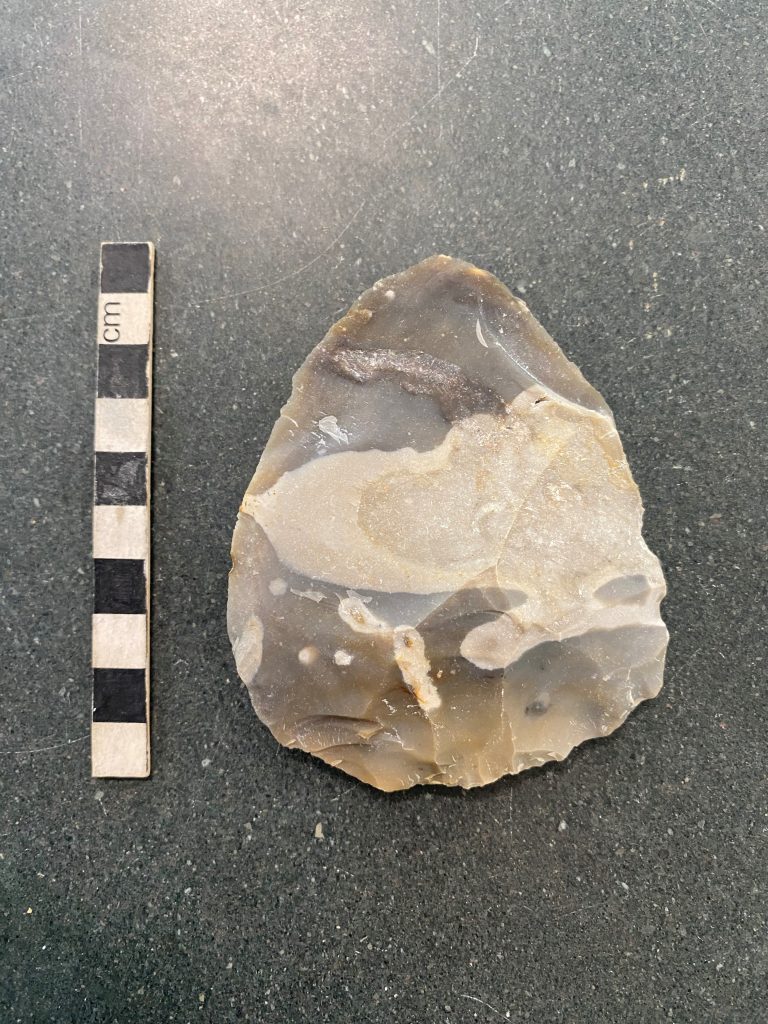

However, to start at the beginning, initially I presented a series of handaxes to the participants, both replicas I had made and ‘real’ ones from our teaching collection. These are used to introduce how stone tools were used historically to understand and create a prehistoric chronology. If we take a step back and think about the structure of the session, a group of flintknapping beginners are presented early on with models of ‘correct’ form, explained by myself, a perceived ‘expert’.

To shift the discussion slightly I would like to introduce the phrase ‘Like mom’s apple pie’ as it is interesting to me on two levels, it uses an outcome (an apple pie) or experience (eating the apple pie) to characterise something as inherently ‘correct’ or ‘positive’. It also links generationally, looking backwards to find a ‘correct’ or ‘positive’ model.

So, to link together apple pies and handaxes it would seem to be a common process to identify past examples as an ideal with which to measure present output. This further links to the work of the anthropologist of art, Alfred Gell, who argued that aesthetics is culturally specific. He goes on to argue that aesthetics serve a social function, and are imposed upon objects so that those objects can be used to achieve some social goal.

If we also consider the typological approach, using particular types of objects to denote particular epochs of prehistory or human culture groups, I would argue this is following a similar model. An ‘expert’ has identified certain more or less measurable parameters which certain objects sit within, and others outside. Those objects that fall within are categorised as one particular period or culture group, those outside may be outliers, or belong to a different period or culture group altogether. This system was developed early on by pioneers such as Gabriel de Mortillet using museum collections. By the 1930s field archaeologists were using an object’s archaeological context to help clarify the above models, and by the 1950s archaeologists were looking to process, in order to understand at what stage in its lifecycle an object sat. Famously, this can be in contrast and conflict to the typological approach, as the object changes shape and form as it wears down through use and then re-sharpened.

To return to our workshop, participants are presented at the beginning with idealised models that carry authority because of the context of presentation (University of Manchester Archaeology Laboratories), and the skilled practice they embody. They also carry with them an aesthetic, and for the replicas produced by me, it is my aesthetic. This is separate from any butchery process but clearly embedded within an archaeological teaching and learning environment, and the history of European stone tool research. My stone tool aesthetic is a modern complex of academic models, bodily practice in negotiation with a range of materials, resulting ultimately in a selection of examples I am ‘pleased with’ and presented to the participants.

As the workshop proceeds the skilled practice that the examples embody becomes apparent to the participants, as they attempt to achieve a similar result. Shape, size and form present a model of idealised outcome that participants strive to achieve within a limited three hour window. For teaching and learning purposes I spend the last hour or so making sure everyone goes home with a functional cutting tool, so that they understand that flintknapping is a game they can win.

Back to aesthetics as a form of cultural control. My knowledge of the history of prehistory and the differing theoretical approaches has been shaped by a western Undergraduate, Masters and Doctorate education in Archaeology, theory and lithics. The development of my ability to make stone tools is discussed elsewhere, but the selection of aesthetic examples is indeed designed to elicit certain social responses, a subtle recognition of my ‘expertise’, and therefore a positive consideration of my guidance. Within this reading aesthetics has been something I have interacted with throughout my lithics education. Certain people, objects, texts and drawings will have influenced my aesthetics over the years and I now perpetuate this emergent aesthetic through my own teaching in the present. As such the Western European idea of a handaxe is perpetuated through time and from one generation of archaeologists to the next. To basterdise the 1819 definition I am both consciously and unconsciously selecting and perpetuating a: ‘set of rules or standards by which a handaxe is judged’.

I have started walking to work and there is a lot of this kind of stuff going on in my head at the moment!

Leave a Reply