My understanding of how to hit things has developed not through flintknapping but martial arts. Consequently, this also influences how I teach other people as I find the principles to be transferable. The first issue is cultural, that generally we are taught that hitting is a bad thing, and so we don’t get that much practice. A first step then is to just get people used to hitting flint with a hammerstone and I have previously done a whole two hour session at Chester on just that.

I then move on to a discussion of impact, or kinetic energy. My understanding is quite processual, in that kinetic energy is a result of the relationship between the mass of an object (hammerstone) and the speed it is travelling upon impact. Whilst the mass of your selected hammerstone will be constant, one variable we can play with is speed at impact. If we remove angles and accuracy from this discussion, a high impact speed increases the kinetic energy, and this in turn increases the chances of getting a clean flake removal. To increase the speed of the hammerstone it is necessary to have a relaxed arm, and relaxation comes from a familiarity with the hitting process (see paragraph one). So far, so good.

Anyway, I was at home and most of my knapping gear is at work and I was feeling a little bit stressed and saw a nice tabular piece of material in the back yard. I am 99.9% sure I picked it up at the Mynydd Rhiw site earlier this year, but my problem was that I only had a very large and very small hammerstone to hand, and a small antler hammer that I usually use on glass. None of the tools were ideal but I wanted to have a go, and if my above theoretical understanding was correct, I should be able to adapt my speed of hitting to compensate for the overly large or overly small size of the tools being used.

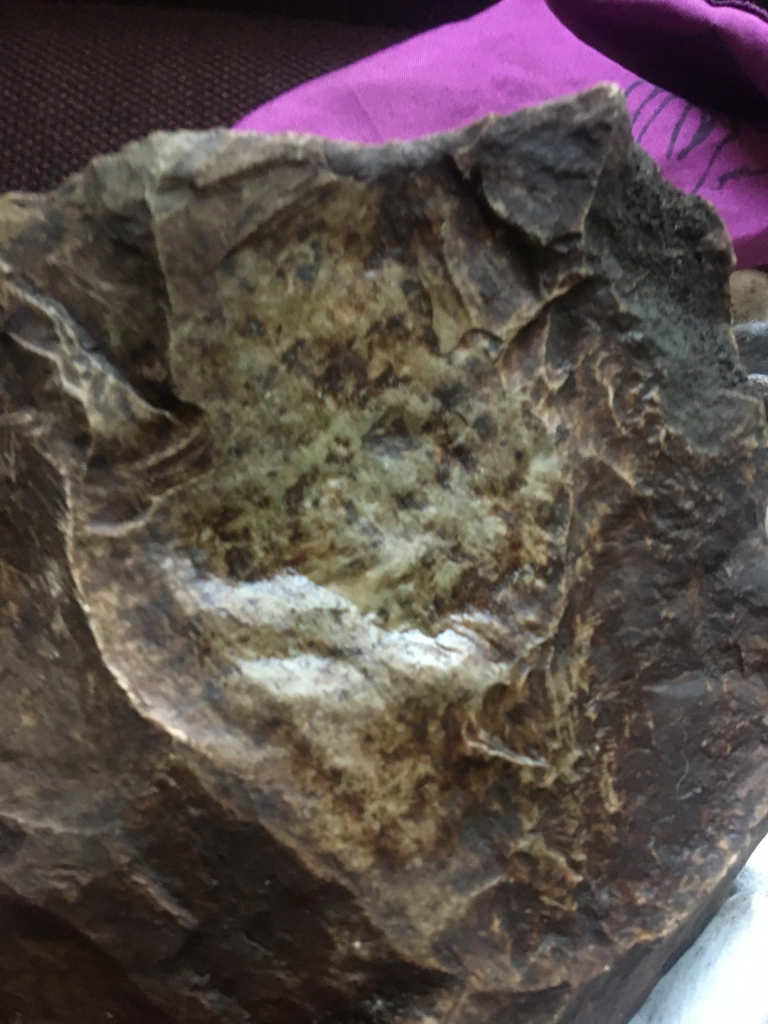

So that is what I did. The large hammerstone was good for the first stage of cortical removals. As you can see, each of these pieces has between 80% and 100% of cortex on the dorsal face.

The next stage was a little more tricky, as I could have done with a slightly smaller hammerstone and larger antler hammer for the shaping and thinning process. As you can see, these pieces are characterised by around 50% cortical surface and they are generally smaller.

With the final stage I really had to hit the material hard with the small antler hammer. A bigger one would have worked better, but my approach succeeded and I did manage to get some nice soft hammer flakes off. As you can see, these are characterised by minimal cortical surface present.

Anyway, if the material was indeed from Mynydd Rhiw I should have made a Neolithic polished stone axe, but being me it became a small flat based cordate handaxe. This is technically incorrect because the material was originally quarried even though I picked it up from the surface. At one point it had a large step on one surface, which I removed by replacing a removal and using that as a punch to get rid, and it worked really well.

The speed thing does work, but it is hard work, and the intuitive way I normally select the appropriate tool does save me energy. There is more to hitting than this, I deliberately avoided a lengthy discussion of angles and accuracy, however this post does go some way towards exploring and explaining (my understanding of) the underlying complexity of what is generally perceived to be a simple process.