Vulnerable-people, System change, Waste materials

Two weeks ago I had a day off work, which is absolutely unheard of for me. I woke up with intermittent pains in my chest, and as they were intermittent I was probably going to drive over to Chester to do my lecture anyway. Fortunately, I am part of a family and after a call to my doctor, Karen and Roxanna decided that a family day out to Accident and Emergency (A&E) was in order. Over seven hours I had an electrocardiogram, blood tests and a chest x-ray. I was able to observe these processes almost dispassionately. I was in no pain, and if there was a problem I was in the right place. In relation to me there was nothing serious to worry about, but I still have to find out what is causing the pains. As a visitor to A&E for the day it was both amazing to be looked after so well at a potentially critical moment, but also eye opening to see how they are managing to manage. As well as really busy and competent care professionals I spent the seven hours with a large number and range of individuals with a variety of distressing conditions and behaviours. There was a lot of vulnerable people and the less urgent cases will have spent a lot longer than me in there.

Fast forward to today, this is my fifth day of recovering from a really horrible flu bug. On Monday I had a snotty nose, Tuesday and Wednesday I couldn’t get out of bed. When I did get out of bed on Thursday I couldn’t walk because of lower back pain. Today is Saturday and I took the dog for a walk around the park. My lower back was really limiting movement and I was feeling very vulnerable to slipping on the patches of ice left over from last night. Last week I was dispassionately observing vulnerable people in physical distress, and today I was the vulnerable person in physical distress. I felt like one of the many and various people I had observed in hospital.

These feelings seems to have affected my focus because on the way back from the park all I could see was the amount of litter on the street. Being an archaeologist I think I can see a pattern. Car pulls up, driver consumes fast food, drink and cigarettes, winds down window, deposits empty packaging on the pavement, drives away. This may be an artefact of a new kind of work where drivers are living in their vehicles for most of the day. It is also incredibly selfish behaviour that makes me very angry. I have yet to see someone doing it which makes it even more frustrating to deal with.

My feelings of physical vulnerability and recent hospital experience made me realise that it is lower paid and older people (like me!) who come to rely more and more on services like the National Health Service (NHS). The deliberate underfunding of the NHS by our government is a clear strategy to turn an encompassing public service model into a profit making business one. By selling off significant elements of the service to the private sector it becomes a business model that profits from the physical vulnerability of an increasing poor and older population. Perhaps because I suddenly saw myself in this ‘new’ (poor and old!) situation it made me consider all those physically vulnerable people and the future of the NHS.

In my fevered and physically vulnerable state I imagined a clear correlation between the discarded packaging ending up in our street, and the various and vulnerable people ending up in A&E. Trafford Council will ultimately pick up the discarded packaging, and the NHS will deal with those vulnerable people, but both will spend a lot of time waiting to be sorted out.

I want to suggest that both these issues are structural in nature. I believe a modern attitude has been cultivated to understand ourselves as individuals first, and to a lesser degree part of a larger society. We are encouraged to become ‘entrepreneurs of the self’, creatively selling ourselves as a product within the wider capitalist market place. Until of course we are no longer ‘useful’ within that market place, something that is dawning upon me as a 61 year old man.

Within this argument, health insurance becomes a ‘technology of the self’, necessary to maintain the functioning of the individual. The discarded packaging are the remains of differing technologies of the self. The single use individual portion coffee cups, plastic bottles and cigarette boxes have all served their single use, and can now be dealt with by someone else. That someone else is larger society, something largely missing from the entrepreneur of the self narrative.

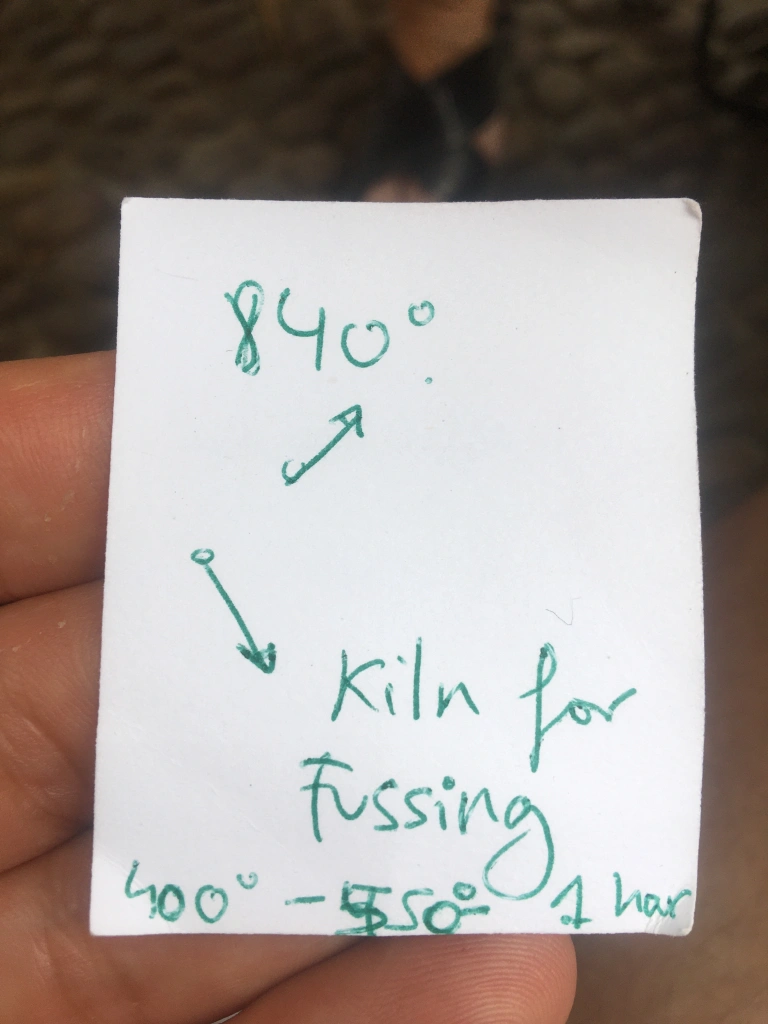

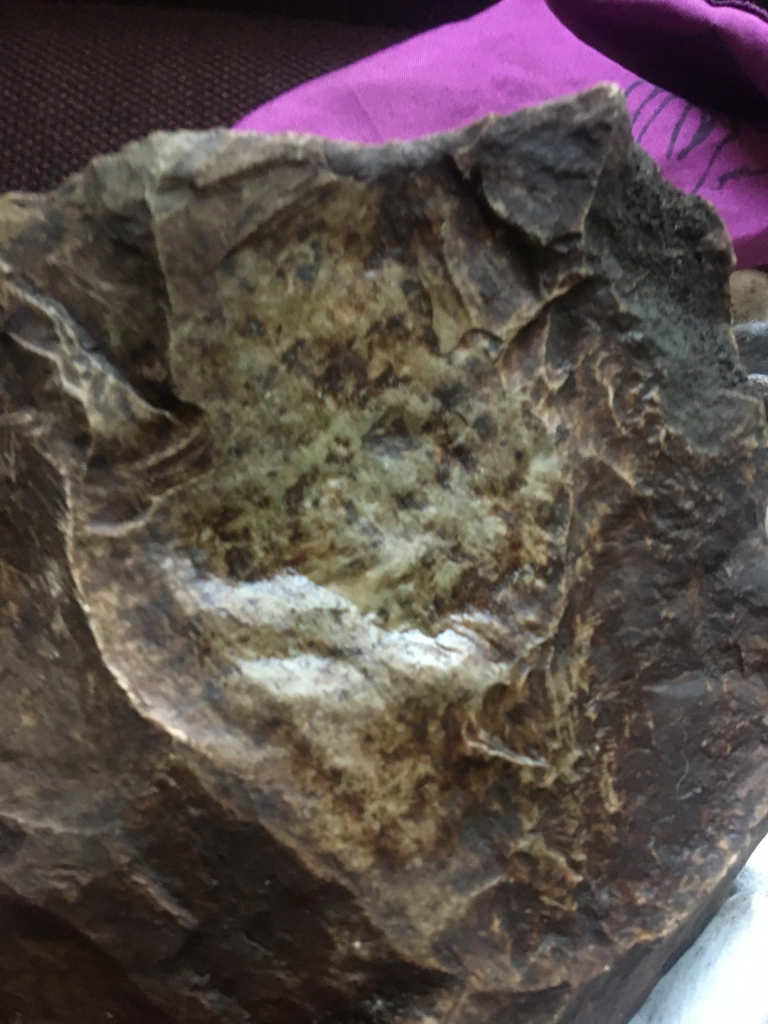

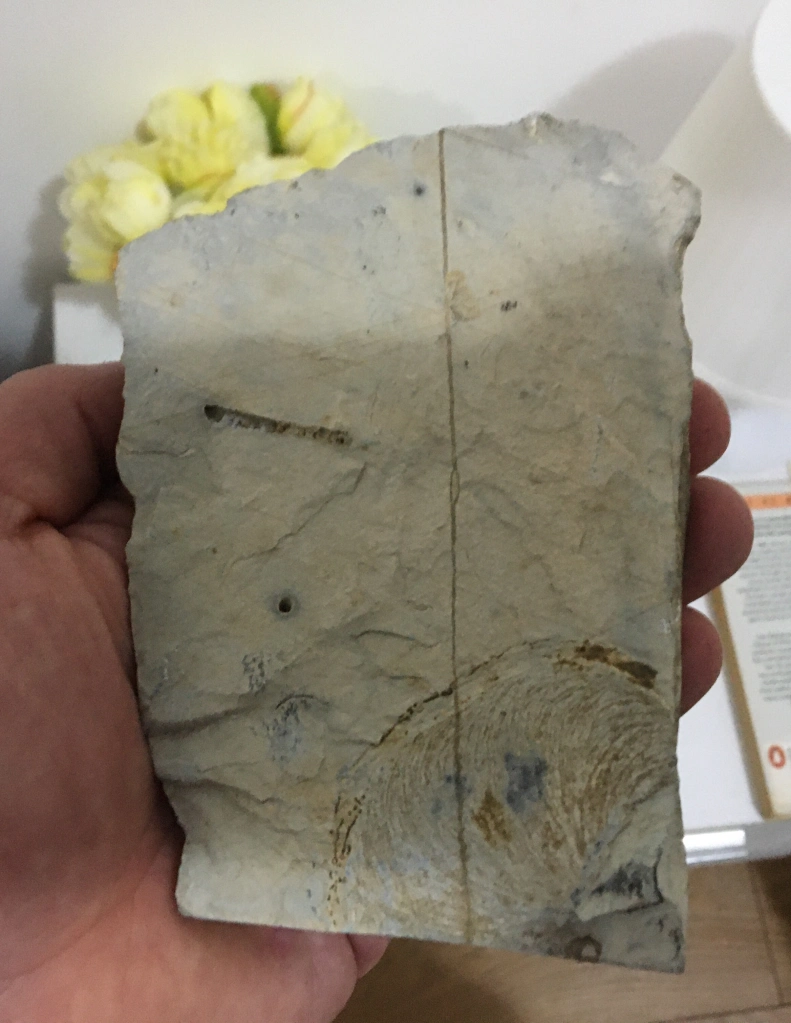

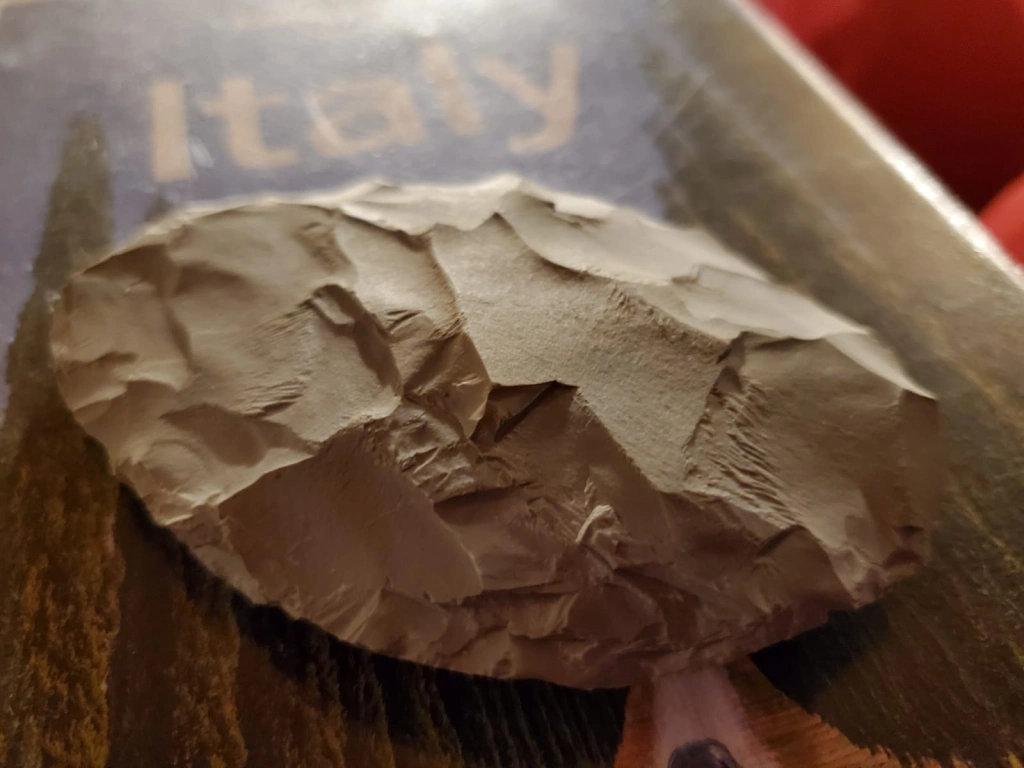

So what does all this mean? It felt like it made sense in my fevered state. Trying to unpick it is a bit more tricky. However, the thing that stands out for me is how virtually all my stone tool making equipment and materials is repurposed waste. It seems that following aboriginal cultures, it is possible to find satisfaction, value, and beauty in repurposing those materials. Developing this idea suggests we could organise things differently. Perhaps a society that was designed to find the value and beauty in both discarded materials as well as older and poorer people. A society like that would certainly be better for those vulnerable folks like myself ending up in A&E, but also for people like my 20 year old daughter, Roxanna. She is fit and healthy but through no fault of her own is going to inherit the looming environmental crisis we are busy creating, one single use plastic bottle at a time. I think we need a system change.