I am leading seminars at the moment on an undergraduate second year module at Chester called ‘Communicating the Past’. To complete the module, students have to produce a 1000 word essay discussing the academic sources used for a proposed Key Stage 2 primary school children’s prehistoric activity. They also need a 2000 word plan for the primary school teachers, showing how the children’s activity works, and fits within the curriculum. Finally, they need to produce a 1000 word reflective piece outlining what the students themselves have learnt from the process. I want to use this post to illustrate why I find reflective learning a valuable tool at all stages of the academic process, and beyond.

To do so, I am going to use an activity I have developed for undergraduate archaeology students to introduce them to the stone tool making process. This 50 minute activity involves around 15 students each making a flint scraper and it is assumed they have no prior knowledge of the process. Having run this session over a number of years, it was only at the most recent session at Manchester where a discussion with a student made me reflect and then rethink and develop my understanding of the teaching process.

To link with the module outcomes necessary at Chester, I have broken this discussion down to consider three key elements:

- The value of academic texts

- Explaining a curriculum activity

- Reflecting on, and learning from the process

For the purposes of this blog post, I am going to start with the activity plan and how I relate it to an undergraduate archaeology curriculum.

My activity plan and how it relates to the archaeology curriculum

I primarily use this activity to introduce the students to the bodily process of making a flint scraper. However, it is also useful on a number of other levels. In particular: as an introduction to the terminology associated with a flint flake; to understanding the relationship between material, kinetic energy and angles within the making process; but also to show how our modern western understanding of a scraper is both historically and culturally situated. These elements feed into undergraduate archaeology modules at both Manchester and Chester (e.g. Doing Archaeology 2, HI4001) and within the actual session I deal with the theoretical bit at the beginning using three Powerpoint slides.

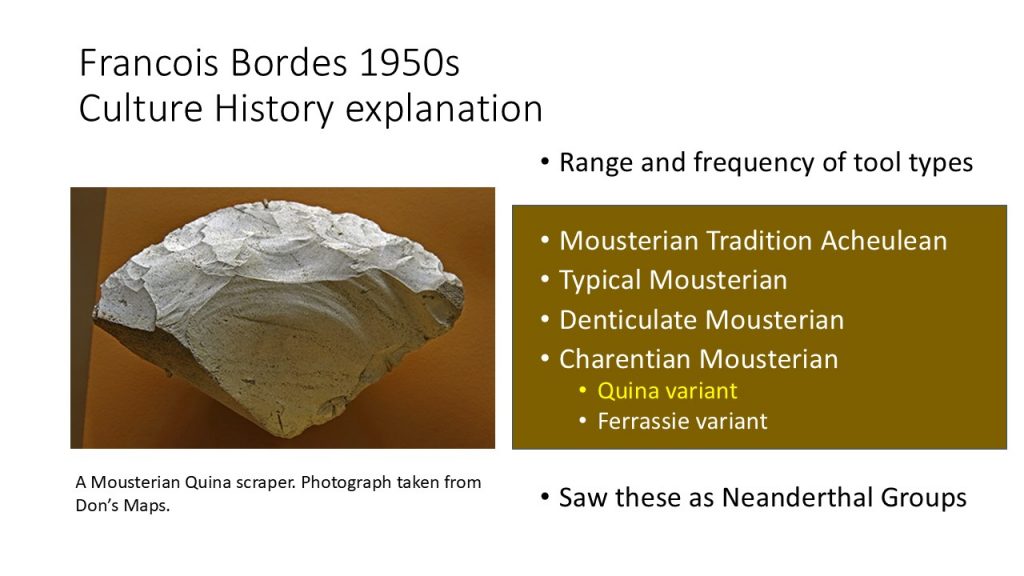

Figure 1. Francois Bordes and a Culture History approach

This first slide (Figure 1.) references the 1950s work of French prehistorian and flint knapper, Francois Bordes, who saw a particular type of scraper, in this instance one he categorised as a Quina scraper, as representative of a particular Neanderthal group. I use this slide to illustrate the ‘Culture History’ approach to interpreting artefacts.

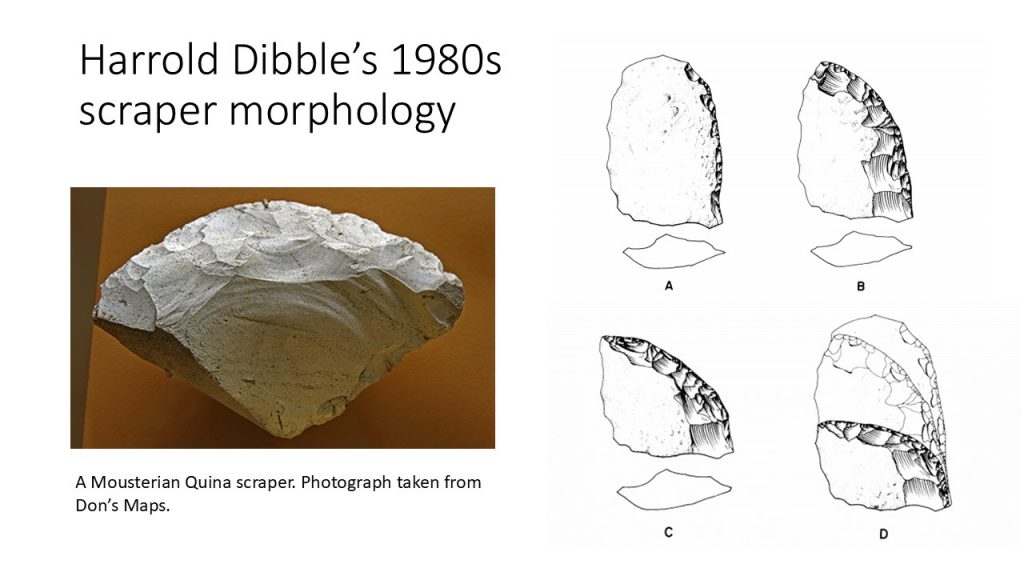

Figure 2. Harold Dibble and the Processual approach

The second slide (Figure 2.) references the 1970s work of the American flintknapper and researcher Harold Dibble. Dibble was interested in the life cycle of the scraper, in particular how the shape changes as the scraper is used, and then resharpened (see illustrations on the right hand side of the slide). He used the fact that shape was dynamic and not static to argue that it was not so useful to think of scrapers as typological signifiers for culture groups. I use this example to illustrate a ‘Processual’ approach to archaeology.

Figure 3. Anthropology and an Aboriginal Australian approach

The third slide (Figure 3.) takes an anthropological perspective, and looks at how Australian Aboriginals would be concerned not with shape, but things like material colour and texture, as well as edge angle. As the slide outlines, totemic ties, kinship relations and what the scraper was designed to be used for, these were the issues an Aboriginal would be looking at.

After ticking the ‘academic box’ we move onto the making process. I direct the students to the necessary protective equipment before providing a demonstration. I select a large flake so everyone can see my process, and explain the difference between the smooth ventral and scarred / cortical dorsal surface. After highlighting the platform and bulb of percussion, I use a felt tip pen to draw the desired scraper shape onto the ventral face, with the bulb of percussion as the potential ‘handle’ (Figure 4.).

Figure 4. A large flake with scraper shape outlined using felt tip pen

I then select a hammer stone, show the correct angle to hold the flake, ventral surface uppermost, and start taking removals from the edges, moving towards the central felt tip outline. As I encounter thicker areas, I draw attention to how the sound changes, and then provide a discussion of how to hit things effectively. Once the desired shape has been achieved, I use a coarse sandstone to abraid away any sticky out bits. Finally, I demonstrate scraper use on a thin birch branch removing the bark. After the demonstration, the students select their own flint flake and hammerstone and then have a go.

Reflecting upon what I have learned from this process

Going around the students, I check where they are up to and help them overcome any difficulties, such as how to hit harder or more accurately. One student had finished his scraper and scraped the branch, but I could see his scraper was blunt, and the edge he had produced was not at an ideal angle for scraping. My diagnosis was that he had held the flake at an incorrect angle when making the scraper. This was not the end of the world as we could remedy this when he re-sharpened it. However, it made me start to think. I learnt how to make a scraper from the professional flint knapper, Karl Lee, and he emphasised the angle at which to hold the flint flake to produce a useful scraper. As discussed above, I have repeated this instruction to students over the years but without considering the Aboriginal perspective that I present at the beginning of the session (figure 3). I have unconsciously absorbed the idea that there is one correct angle to hold the flake in order to make a scraper. However, if the slide about Aboriginal knappers that I present is correct, then there must be more than one way of holding the flint flake in order to get more than one edge angle. Why had I not recognised this before? Probably because I am not using scrapers in practice and so I am not so knowledgeable about the different uses, and therefore the various edge angles.

The academic sources I am using

This leads to the interesting bit. Because I have been delivering this session over a number of years, I could not remember where I had read about the Aboriginal perspective on scrapers. This is obviously a missing component that could really enrich my session, so I am now at the stage of having to find out more information. Being a big fan of the social aspects of archaeology, my first step was to email my main contact in Australia, Kim Akerman, an academic and stone tool maker who has been really helpful to me in the past by directing me to relevant sources when I was originally looking into Kimberley Points. I would always encourage people to contact specialists in the area they are interested in, however, this is another story. Using the library search facility and term: Aboriginal Australian scraper edge angle, I am currently working through the relevant papers that come up, with the aim of understanding more fully the Aboriginal relationship with edge angle and tool function. I can then integrate this knowledge into my undergraduate scraper making exercise.

Concluding thoughts

I emphasise reflective learning because I think it it illustrates how both teaching and learning is a process, not a product. I have a stone tool based PhD, am a competent stone tool maker and have been teaching undergraduate archaeology modules for the last six years. Whilst I have a good level of archaeological knowledge and understanding, I am absolutely still on my learning journey. As part of the PhD process, it is necessary to learn about teaching theories and learning styles, to understand the range of ways we learn, and therefore the range of ways we can teach. One of the most useful learning styles I have adopted is that of David Kolb and his experiential learning cycle. Kolb’s learning cycle has four stages. He presents an initial ‘active’ or ‘concrete’ phase of doing, let’s say, making a scraper. This active phase is followed by a reflective phase, considering how things went, and what changes to process could be made so that a better end result is achieved. The third phase of Kolb’s cycle involves doing the activity again, but this time integrating the considered changes to the process. The fourth phase is again reflective, looking at what has been produced and considering whether or not the change to process has helped to achieve a better end result, or scraper.

At first encounter, the reflective process can seem passive, sat thinking, devoid of action. I have found writing this blog / website a useful and active reflective learning tool that has really helped me develop my understandings. This has been primarily in relation to learning the stone tool making process, but as you can see with this post, also with my teaching and learning within archaeology more generally. In other words, doing something, like making a scraper, then writing about the process, is valuable in helping us to learn. Funnily enough, this is exactly what this Chester module is asking students to do; to develop an active reflective process. As discussed here, reflective learning is a strategy that has value at whatever stage of the academic process you are working at, and I would argue, beyond a particular subject area. Many archaeology students go on to work in areas beyond archaeology and the aim of this blog post is to illustrate the value of learning strategies as well as subject specific knowledge. For those who are interested, this link provides more information on David Kolb’s learning cycle, and experiential learning in general.

Leave a Reply