This week we had an experimental session with second-year ‘Themes’ students in Chester making some clay Palaeolithic Dolni Vestonice ‘venus’ figurines (and associated wolverines and bears). Nacho came over with me from Manchester and the topic we used the making process to explore was that of Personhood. How we as modern westerners understand the category, but also thinking about how people in the Palaeolithic past may have done so. And a number of interesting ideas emerged.

A 2017 scan (see link below) of the ‘venus’ revealed that it had been made from one piece of material, as opposed to having bits stuck on to create the arms, legs, breasts etc. This was something Paul Thomas talked about in a previous workshop and demonstrated how squeezing the clay brought out particular shapes that could then be ‘pulled’ into shape. This contrasted to the approach many of the students initially took this week, adding clay to the models to build them up. I think it is fair to say that everybody (including Nacho) had difficulties creating a model ‘venus’ that was correct in size and form. However, after initial difficulties, and once people had got a feel for the materials a menagerie of animals emerged. This cat for example seems to have started out as a wolverine or bear, but then morphed into a cat. People seemed to find it much easier to create a shape from the clay that corresponded with an animal they knew, rather than emulate photographs of the originals. As Nacho pointed out, that is exactly what people in the past were doing, and so in many ways figurines like the cat below are more representative of the original process than a super accurate wolverine or bear replica.

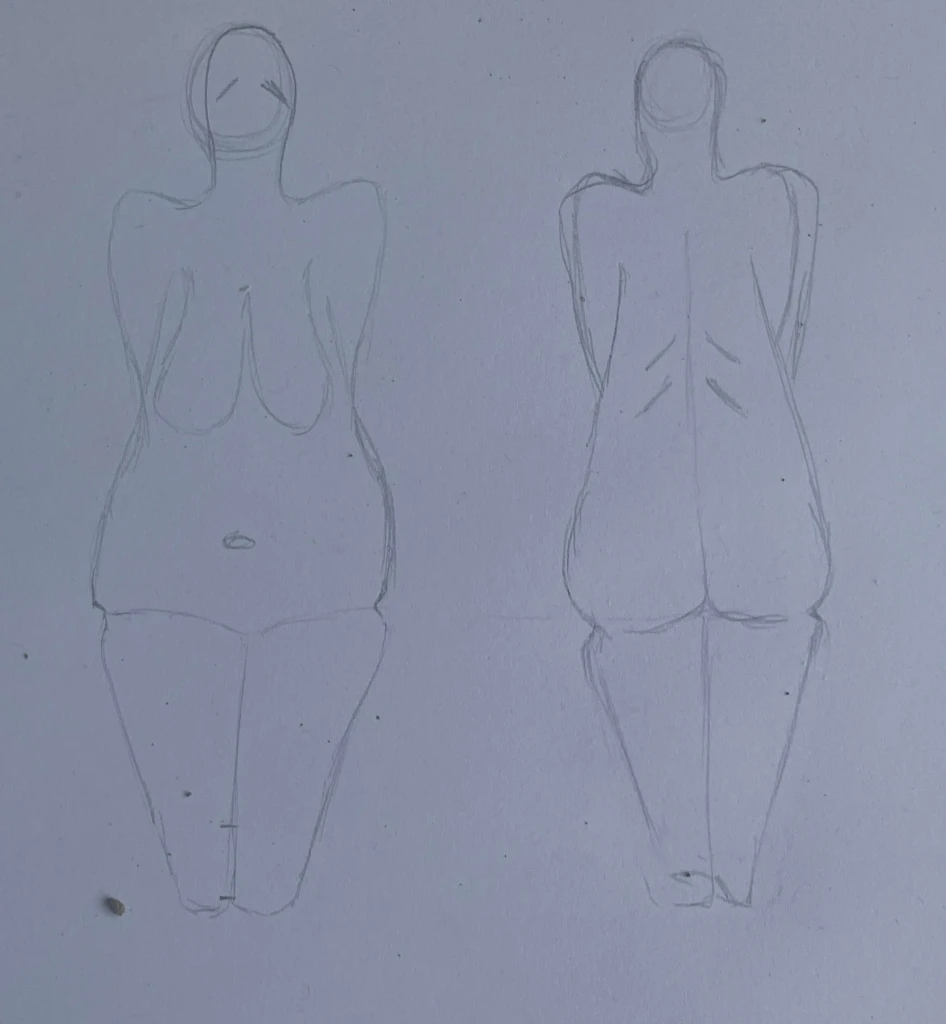

In relation to the ‘venus’ we asked people to draw the figurine first, as a way of seeing the key elements before embarking upon the making process. In the discussion section at the end Elowyn said that she didn’t see herself in the figurine, and felt as though it was referencing an older female form. Jacob suggested it represented a woman’s body after having gone through the process of childbirth, and we all agreed that the lack of facial detail meant it wasn’t an individual portrait but representing a category of women. This was interesting from the personhood perspective because it suggests Palaeolithic womanhood comprised different facets perhaps organised around age bands and the process of childbirth.

It was also interesting that towards the end of the session Elowyn made Victoria a present of a miniature bear, and then gifted it to her. This allowed us to think about the potential of the original ‘venus’ having been a gift, and about what possible qualities may also have been given along with the figurine? We had discussed the Soffer (et al. 1993) paper arguing that the figurines may have been deliberately exploded during the firing process for divination purposes. Developing the ideas of Soffer (et al. 1993: 39) we thought about whether the gifting of the figurine could have been intended to ensure safe childbirth?

For me, the key idea that emerged from the session was again about the making process and its relationship with the human hand. Squeezing the material allows certain shapes to emerge and these shapes may resemble recognisable animals or person categories. This general similarity can then be developed by literally pulling the material into shape. That the the creation is then fired and potentially exploded provides a really interesting blend of dramatic creation and destruction narratives. And so, far from Nacho and myself ‘delivering knowledge’, it was very much the making and sharing of ideas part of the session that resulted in it being so interesting and enjoyable.

And at this point it is probably apposite to introduce my own personal favourite, Owain’s cheeky bear, and thank Nacho for facilitating the making process and Jacob for being official photographer on the day.

Papers

Soffer, O., Vandiver, P., Oliva, M., and Seitl, L. 1993. Case of the exploding figurines. Archaeology Vol.46(1) pp.36-39.

Links

Leave a Reply